You can Learn to Improvise at the Dungeness Creative Music Workshop, Wednesday Afternoons from April 3-June 5, 12:30-2:30 PM. Register Today. Tuition is only $150 for this 20 hour workshop. Email craig@craigbuhler.com or check out this video for details.

Author: Craig Buhler

A Harmonic Minor Workout

Pianist Dr. J. H. asked for a melodious exercise he could use to explore the harmonic minor scale in all 12 keys. The “harmonic minor scale” features the natural 6th degree FA along with the raised 7th degree. The raised 7th degree in a minor scale is the syllable known as “si” (pronounced “SEE”). It’s also referred to as “#SO” or “#7.” That scale is shown here:

Pianist Dr. J. H. asked for a melodious exercise he could use to explore the harmonic minor scale in all 12 keys. The “harmonic minor scale” features the natural 6th degree FA along with the raised 7th degree. The raised 7th degree in a minor scale is the syllable known as “si” (pronounced “SEE”). It’s also referred to as “#SO” or “#7.” That scale is shown here:

Improvise With The Blues Scale

Trombonist Cindy M. asked me to talk about how we use the blues scale to improvise. Comparing it to the major scale, you see the blues scale features three “blues notes,” notes Mozart would never use.

Trombonist Cindy M. asked me to talk about how we use the blues scale to improvise. Comparing it to the major scale, you see the blues scale features three “blues notes,” notes Mozart would never use.

I Dig This One !

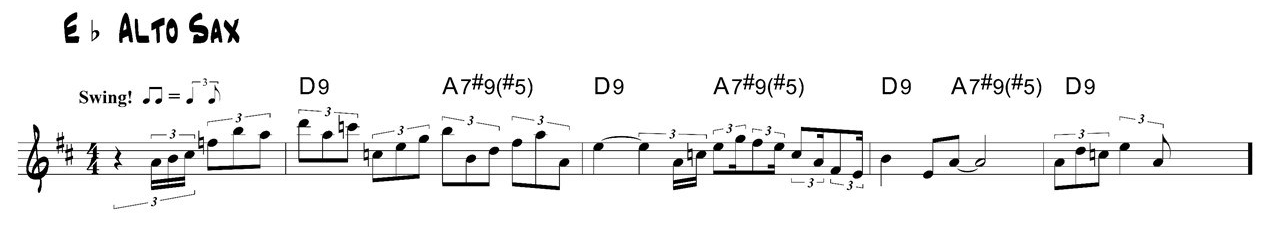

Does improvising bring you joy? If you’re playing music you love, both you and your audience will be swept up in that transcendent joy. Here’s a topsy-turvy, tangled up, spaghetti-shaped, four-bar phrase that just tickles my spirit every time I play it. Hope you dig it too. Click here to watch the video.

Does improvising bring you joy? If you’re playing music you love, both you and your audience will be swept up in that transcendent joy. Here’s a topsy-turvy, tangled up, spaghetti-shaped, four-bar phrase that just tickles my spirit every time I play it. Hope you dig it too. Click here to watch the video.

Mode For Joe

Saxophonist Maria is improvising over Joe Henderson’s classic jazz standard “Recorda-Me.” I asked her whether she would use the Dorian or Aeolian mode over the first 4 bars.

Saxophonist Maria is improvising over Joe Henderson’s classic jazz standard “Recorda-Me.” I asked her whether she would use the Dorian or Aeolian mode over the first 4 bars.

As shown below, the Aeolian is the mode rooted on LA, so it uses a lowered 6th degree. By contrast, the Dorian is rooted on RE, so it features a raised 6th degree.

Fresh Out of Ideas

Tenor saxophonist Brooklyn brought a favorite tune to his lesson. As always, we typed the changes into Band in a Box, chose a tempo and a groove, and started blowing on the tune. But Brooklyn said he was having trouble coming up with fresh ideas to play over the changes.

Slippery Slope

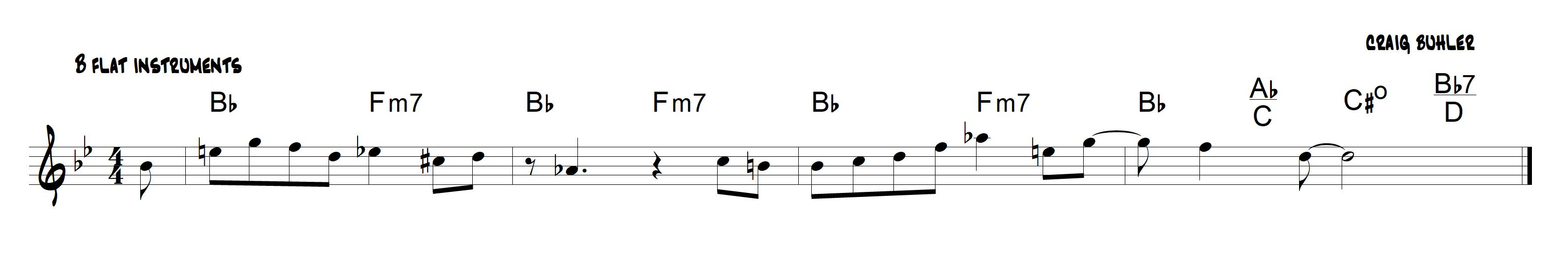

For fans of Brazilian bossa nova jazz, here is a bright bossa composed and performed by tenor saxophonist Craig Buhler. In addition, if you have ever taken a terrible tumble, these ski slope stumble scenes will give you a chuckle and remind you that you’re not alone.

Below is a chart for B flat instruments you can view or download, in case you’d like to perform this song. (For charts in other keys or clefs, send me a comment listing your instrument, key, range, and preferred clef.) Continue reading “Slippery Slope”

Applying Moveable DO Syllables to Jazz Standards

Introduction

Alto saxophonist Pascal wrote requesting assistance with assigning movable DO syllables onto several jazz standards. Before addressing each of these tunes, let’s talk about the reason we use movable DO syllables.

As jazz musicians who play melodies by ear (without charts) and improvise over their changes, we are not concerned with theory for its own sake, as are academicians. Instead, our primary goals are:

Continue reading “Applying Moveable DO Syllables to Jazz Standards”

Fixed DO Versus Movable DO

“I was trained using ‘Fixed DO.’ In other words, if I am playing an E Major scale, I was taught to name the notes ‘MI, FA#, SO#, LA, TI, DO#, RE# MI’. Your book, “New Ears Resolution,” teaches me to think in terms of ‘Movable DO.’ What is your reason for preferring this method?”

Thank you for bringing this point up, Pascal. This is an extremely important question you have asked.

Playing by Ear in Different Keys

Saxophonist Pascal asked an excellent question concerning how to play by ear in different keys:

Saxophonist Pascal asked an excellent question concerning how to play by ear in different keys:

“Regarding exercises involving arpeggios, inversions, or scales on saxophone: When using movable DO, should I think of each tonality as if it were C Major? For example, when I play in E major, do I think, “DO RE MI FA SO LA TI DO”? Is it as if there were only one Major scale on each starting key? This is a revelation for me!”

Good question, Pascal. A major scale has the same specific form, regardless of which note is chosen to be DO. Here is that form shown as a schematic and on the piano keyboard:

Have Fun with ii-V-I !

If your set list includes numbers from “The Great American Song Book,” then you’re going to wrestle with the ii-V-I progression in a bunch of keys. Here’s a winsome ii-V-I phrase to help strengthen your chops, develop your ear, and arouse your creative vocabulary as a improviser. Click here to watch the video.

If your set list includes numbers from “The Great American Song Book,” then you’re going to wrestle with the ii-V-I progression in a bunch of keys. Here’s a winsome ii-V-I phrase to help strengthen your chops, develop your ear, and arouse your creative vocabulary as a improviser. Click here to watch the video.

Did the Key Change or What?

The unpredictable flow of shifting key centers can easily throw uninitiated players off balance, especially when jamming on unfamiliar tunes. CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE VIDEO.

The unpredictable flow of shifting key centers can easily throw uninitiated players off balance, especially when jamming on unfamiliar tunes. CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE VIDEO.

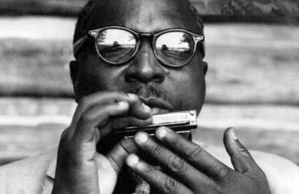

Another Blues Scale

Click here to watch the video.

The blues idiom offered early twentieth century musicians a new way to share deep emotional feelings vigorously and honestly.

A hundred thirty years earlier, Mozart had reveled in the fresh, airy lightness of the major tonality which superseded stolid Renaissance modal forms around 1600.

Periodic innovations like these keep music vibrant and invigorating. Unfortunately, too many of today’s musicians bloat their playing with endless, unimaginative, repetitive blues licks. Sure, blues licks can add a funky edge, but overuse of these clichés leads to tiresome monotony.

(And so on, and so on….Well, you get the idea!)

Mixolydian ?? I’m Mixed Up !

This post defines the Mixolydian Mode and shows how you can use it in your music. Click here to watch the video.

Continue reading “Mixolydian ?? I’m Mixed Up !”

Rhythm 2: Express Yourself!

Swinging rhythms are the foundation and heartbeat of great jazz. Our first “Rhythm” video was a primer on how to play jazz rhythms. Click here to watch it.

In this video, we’ll talk about how you can use rhythm to effectively express yourself: your thoughts, your feelings, your personality, your unique story.

Demystifying Motivic Development

Guitarist Patrick S. asked for some more examples of “motivic development” (MD). Whether you’re a composer, an improviser, or just looking to enliven your daily practice routine, MD techniques can stimulate your creativity and broaden your musical horizon. Beethoven elevated sonata form to new heights with MD, while Sonny Rollins used MD to revolutionize jazz improv far beyond “a bunch of memorized licks” and “sax players searching for the right note.”

Guitarist Patrick S. asked for some more examples of “motivic development” (MD). Whether you’re a composer, an improviser, or just looking to enliven your daily practice routine, MD techniques can stimulate your creativity and broaden your musical horizon. Beethoven elevated sonata form to new heights with MD, while Sonny Rollins used MD to revolutionize jazz improv far beyond “a bunch of memorized licks” and “sax players searching for the right note.”

Let’s take a look at six ways you can use MD to breathe new life into your music:

- Change the Rhythm

- Alter the “Feel”

- Create Pitch Retrograde

- Offset the Rhythmic Pattern

- Fragment the Phrase

- Sequence the Fragment

Rhythm in Your Bones!

If you (or your students) struggle with playing swinging jazz rhythm, this video will go a long way toward gearing up those important rhythm chops. CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE RHYTHM VIDEO.

If you (or your students) struggle with playing swinging jazz rhythm, this video will go a long way toward gearing up those important rhythm chops. CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE RHYTHM VIDEO.

I feel so much more like I do now than I did when I first got here.*

Jazz gigs seldom turn out exactly as we expect them to. Since jazz is, by definition, an improvised art, this should come as no surprise. It’s a maze which often thrills, sometimes shatters, and continually amazes us.

Let’s say, for example, that you arrive at the gig late, stressed, un-showered, and unready to perform. It’s at this point that a fan drops a hundred dollar bill in the tip jar, Herbie Hancock asks to sit in, and your first solo provokes a standing ovation. In your dreams, right?

The nature of jazz will, at times, lead to the unexpected, to exciting innovation, to surprise, to joyful discovery. …Occasionally, it leads nowhere. After all, life’s mazes do include blind alleys. Just the same, we “press on regardless” (as my father often preached on rainy hikes), in search of the perfect note, aye? Continue reading “I feel so much more like I do now than I did when I first got here.*”

BLOW TILL YOU KNOW

Are you struggling to develop a personal improvisatory style or to find your unique compositional voice? Well, you’re not alone! Many musicians grapple with these dilemmas.

Perhaps my own story will help you unearth your path to musical originality.

I started playing because I love the way music sounds, the way playing the horn feels, the exhilaration of working with a great band of like-minded musicians. A couple years later, I began writing songs, just so we’d have originals for gigs and recordings. I didn’t think twice about trying to be original. On the contrary, emulating the masters was satisfying. It seemed to legitimize and validate my work.

However, about 10 years into my career, I suddenly faced an existential crisis, when nagging questions like these began keeping me awake at night:

“Is this composition any good? Is it too long? Which sections are valid and which need to be scrapped? Should that note be a Bb or an F#? Do my solos stink? What right do I even have to compose music or play the horn, when there are so many musicians out there who are way better?”

Chromatic Cro-Magnum P.I. (Practice Improv)

Ever feel totally drained after a big gig with no steam left to practice, like a malnourished Cro-Magnon? That’s how I felt this morning, after last night’s intense concert backing up my friend presenting 14 of his complex original compositions.

Ever feel totally drained after a big gig with no steam left to practice, like a malnourished Cro-Magnon? That’s how I felt this morning, after last night’s intense concert backing up my friend presenting 14 of his complex original compositions.

What’s a person to do? Well, “one foot in front of the other,” as the old saying goes. Just start blowing long tones; dig the sound of the horn, experience the feeling of wind on reed, fingers on pearls.

Here’s what emerged after an hour or so; a little chromatic meander that caught my imagination. As harmonized in this sketch, it forms a Dorian setting reminiscent of “So What,” “Little Sunflower,” “Jeanine,” or “Invitation.” It could also have been harmonized as a ii-V progression in C major modulating to D minor.

Click on “continue reading” below to see a chart and hear the recording in all 12 keys.

Continue reading “Chromatic Cro-Magnum P.I. (Practice Improv)”

Compose, Improvise, Practice: Three Birds, One Stone!

Do you ever NOT feel like practicing? If your go-to staple is a dry method book, you’ll probably answer “yes” – if you’re really honest.

On the other hand, if you dream of becoming an inventive improviser or an innovative composer, then read on!

Continue reading “Compose, Improvise, Practice: Three Birds, One Stone! “

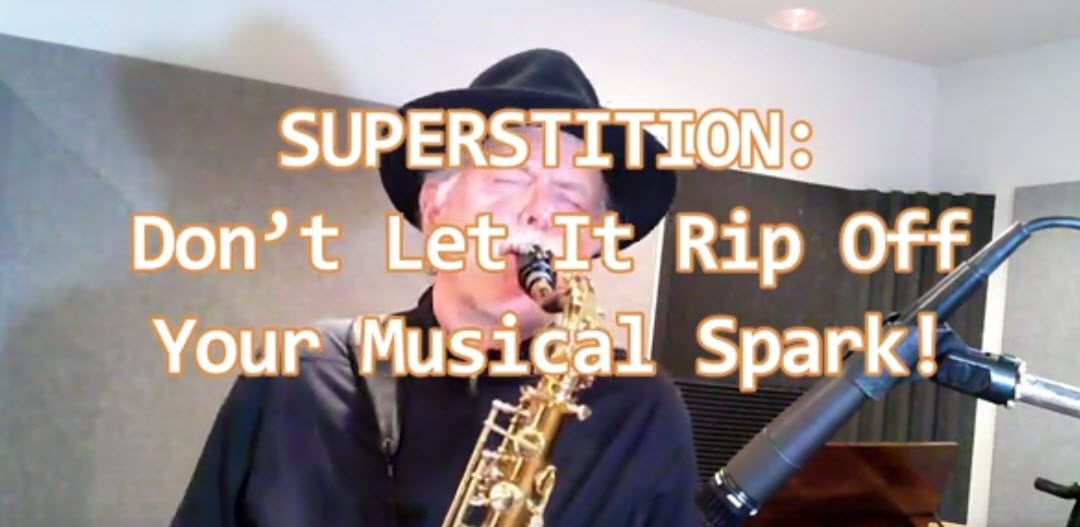

SUPERSTITION: Don’t Let It Rip Off Your Musical Spark !

CLICK HERE to view the video on YouTube. Click “continue reading” below to download the chart and background track or to read the script.

Continue reading “SUPERSTITION: Don’t Let It Rip Off Your Musical Spark !”

Cantabile

It comes from growing up with James Brown, Sly Stone, and Tower of Power:

I prefer punchy, funky, accented articulation and short, clipped, syncopated rhythms.

But comes a time when smooth, cantabile phrasing is on the menu. So here goes.

If you want to woodshed this lick in all 12 keys, click “continue reading” below to see a complete chart, hear the complete recording @ 180 beats per minute (BPM) as well as a slower complete recording @ 100 BPM.

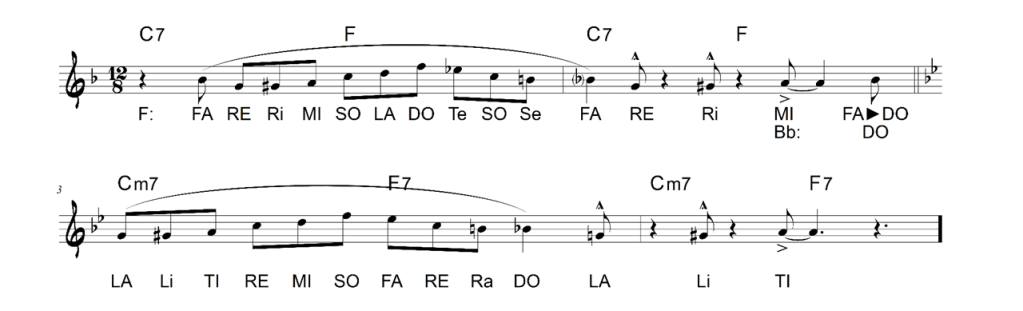

Where’s One?

When a novice improviser strays too far from the beat, the band often quips, “Where’s One?”, meaning “Are you lost?”

As improvisers, we seek fresh, innovative approaches which still retain the coherence needed to keep listeners’ interest. Sonny Rollins famously used “motivic development” to simultaneously add unity and variety to his improvisations.

Here is a melodic phrase which is then repeated verbatim. What makes the second statement of this phrase sound different from the first?

Notice the “rhythmic offset”: the initial statement of the theme begins on beat 3 (we’re in 12/8), while the second statement begins on beat 12. Jazz players call this “playing on the other side of the beat.” If your band mates are sufficiently skilled to avoid getting lost, playing on the other side can be used to stunning effect.

Note also that the second statement of our melodic phrase – while melodically identical to the first – is accompanied by chords from a different key. We might refer to this as a “transposed harmonic setting.” The new harmonies give the melody a distinctly different sound, as if stage lighting on an actor had been changed from red to blue.

Practice Joy-Subconscious Symmetry

How’s your practice routine feeling lately? Are you practicing joy? If you practice joy, your audience will hear joy in your performance, and that lively winsomeness in your playing will win you way more fans than all the chops in the world.

Students ask what I mean by “practice joy.” Of course, it goes without saying that you need to develop your technique. But music is way more than just chops.

It may help to think of your practice session like a lavish banquet. …(we didn’t have many of those in 2020!) Think of it in 3 parts.

| Your banquet | Your practice session |

| 1. Introductions, greetings, catching up, small talk, hors d’oeuvres, drinks | 1. Your warm-up, settling in, loosening up, getting in the groove |

| 2. The main course | 2. Working intentionally through an idea or challenge |

| 3. Coffee, dessert, farewells, hugs or hand shakes | 3. Reward yourself with a fun little jam! |

Doesn’t that approach sound more doable, more inviting, more intriguing than staring forlornly at a closed horn case, wondering how to drum up energy to open that case and start playing boring scales?

Those 3 parts of your practice session remind me of Oliver Wendell Holmes’s comment about how a simplistic idea develops into a complex struggle but then resolves into a simple but elegant design.

So how about let’s design a practice routine so enthralling — so much fun — that you just can’t wait to pick up your axe and blow! As one typical example, here’s a practice session from a couple days back which was both productive and immensely enjoyable. Every day isn’t exactly like this. Sometimes the focus is on long tones, sometimes it’s reading through transcriptions, etc. But – on this particular late evening session – I followed Sonny Rollins’ advice. Sonny said, “just start playing the horn. Listen to the sound. Feel your breath and the keys of your axe. Play a blues. Play a tune. Play any old licks that come to mind.” Rollins called them “clichés,” but he didn’t mean that as an insult. They’re the bread and butter of learning. Don’t evaluate, don’t judge, just relate to your axe and enjoy how it sounds, how it makes you feel. After I blew for awhile, this lick just popped out.

I kind of liked it, so I kept repeating it. Maybe I tweaked it as I went along, I can’t remember. After getting it smooth in one key, I ran it down in all 12 keys. Then I wrote it down in my journal, knowing full well I’d forget it otherwise. After a day or two, I looked back at the transcription and discovered an inner logic — the thing that makes a phrase seem natural and organic – that I hadn’t noticed before. Up to that point, I’d just been blowing, without a sense of compositional coherence, or any of that theoretical stuff. But there it was, the musical logic, just waiting to be discovered…

Subconscious Symmetry

Below is a recording of me playing this phrase in all 12 keys along with a chart. After that, I discuss the logic hidden within this unusual phrase.

Blues in Benny Carter’s Heart

Benny Carter blessed us with an amazing solo on the 1938 recording of his composition “Blues in My Heart.” The entire performance is miraculous, but one four-bar passage in particular knocked me out, prompting me to shed that phrase in all 12 keys. Here’s the lick:

Benny Carter blessed us with an amazing solo on the 1938 recording of his composition “Blues in My Heart.” The entire performance is miraculous, but one four-bar passage in particular knocked me out, prompting me to shed that phrase in all 12 keys. Here’s the lick:

Benny’s rhythmic vitality propels the piece, his melodic contour is unique in all of jazz literature, his harmonic inventiveness is preposterously original, and his crystal clear tone is infectious. Here is my transcription of those amazing four bars.

Here is a slowed down recording of that phrase in all 12 keys:

If you want to play it yourself, click the “continue reading” button to see a complete chart.

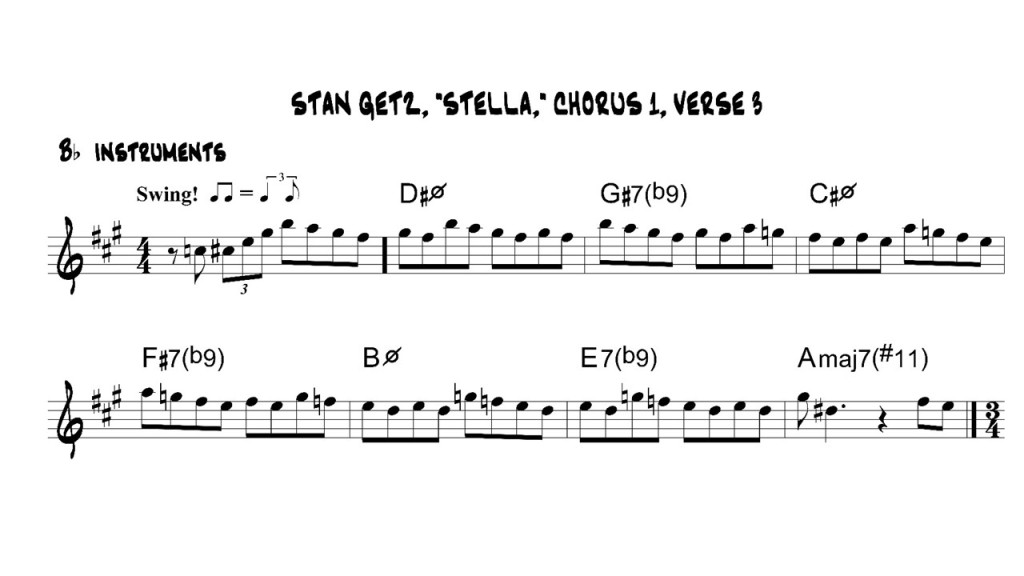

Stan’s Stella Sequence

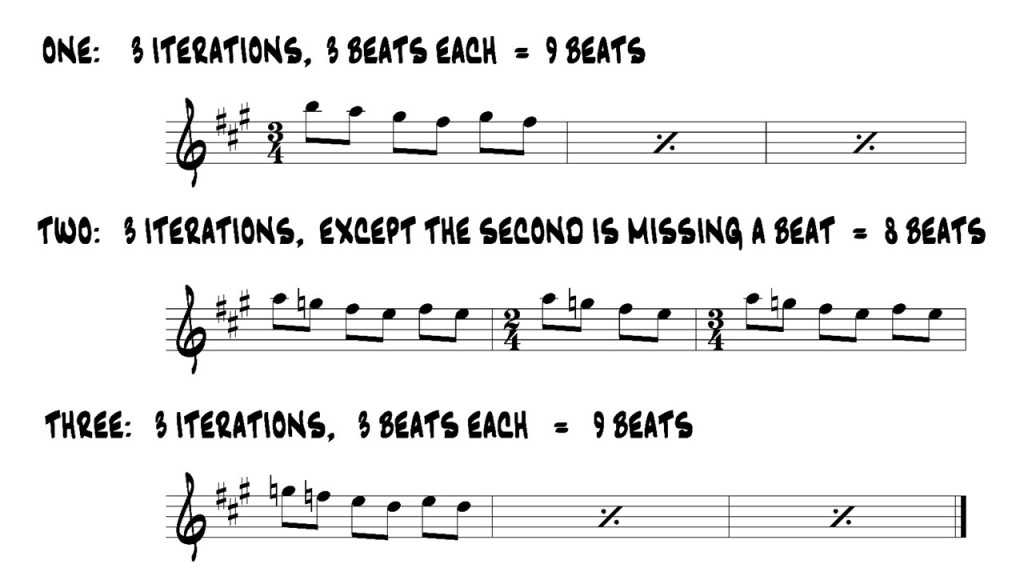

Yesterday, I discovered a sequence in Stan Getz’s 1952 Clef recording of “Stella by Starlight,” (MGC 137). The three-by-three format unfolds as Stan finishes the bridge on his first chorus. Here it is:

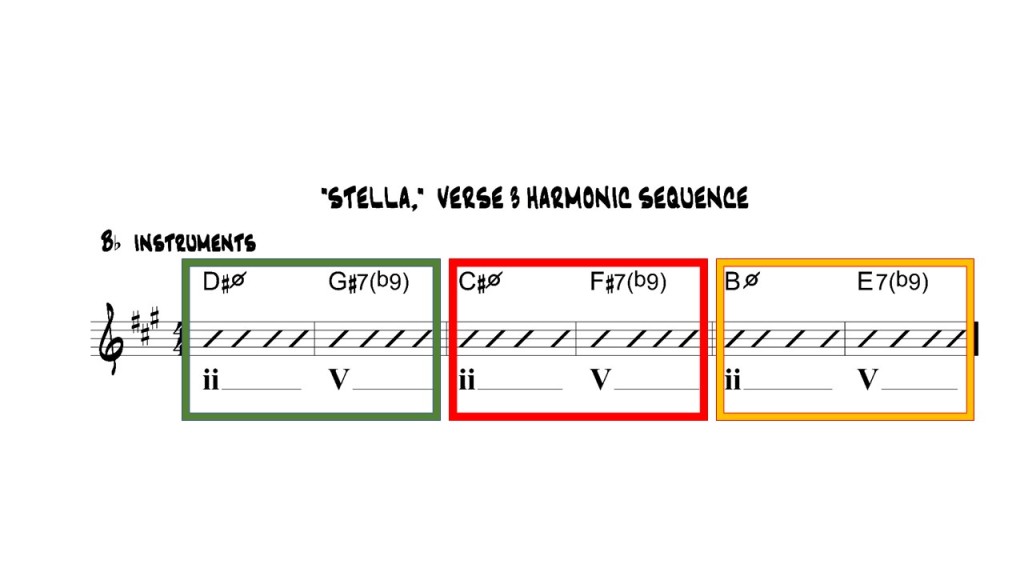

If you’ve studied “Stella,” you know that the final 8 bar section of the form contains the intriguing 6-bar harmonic sequence shown below:

As shown here, that harmonic sequence features 3 iterations of 8 beats each, for a total of 24 beats. But Getz begins his amazing melodic sequence 2 beats before the passage shown above, so he needs to fill 26 beats.

The diagram below illustrates the incredible way he accomplishes this Herculean feat. Stan’s motif of six eighth-notes covers 3 beats and is repeated three times on each of three starting notes. But on the second iteration of round two, he leaves out a beat. Thus, the total episode comprises 9 + 8 + 9 = 26 beats. Even at 160 beats per minute, Getz is able to execute this monumental feat so smoothly that it sounds effortless.

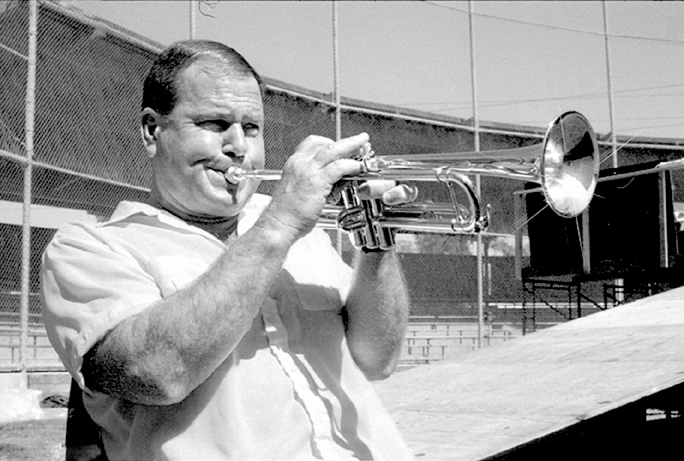

Listen and Learn

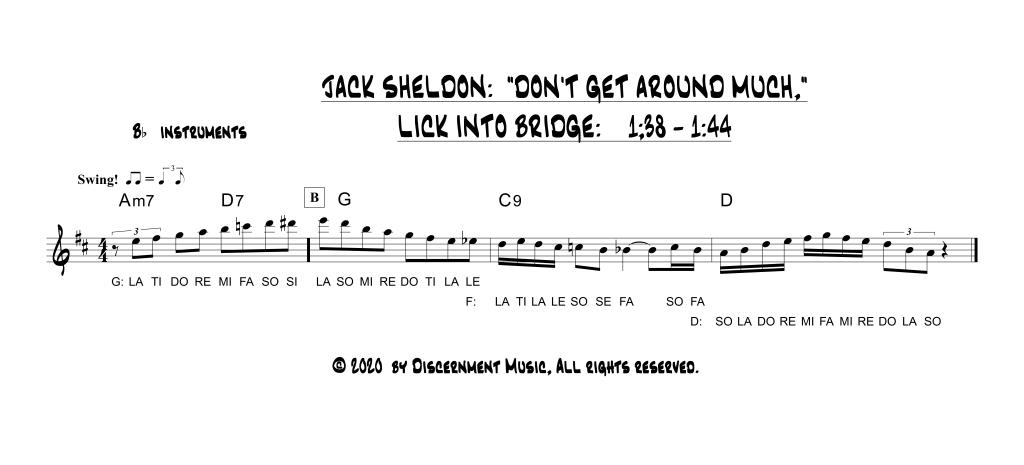

If he’d survived, trumpeter Jack Sheldon would have turned 89 on November 30th, 2020. For one who never studied his recordings, it’s fascinating to watch a live video of his quintet in concert. The five musicians play in perfect sync, like a well-oiled machine, and they swing like crazy. Jack’s vocal style is instantly recognizable, and his trumpet sparkles with fiery assertiveness, crisp inventiveness, and unhesitating self-assurance.

The lick leading into the bridge of Jack’s solo especially knocks me out. Here it is:

There’s a dynamic shape to that melodic line and an infectious rhythmic vitality which combine to offer a wildly exciting listening experience. Equally impressive is Jack’s ability to infer fascinating harmonic curve-balls creating two deceptive modulations before settling onto the home key, as portrayed on the chart above .

Here’s that lick in all 12 keys.

A complete chart is provided below, if you want to woodshed this unique lick.

My friend Bill – an excellent trombonist – voiced his frustration after attempting the licks on my blog at full speed. I reassured Bill that I certainly do not begin by playing any of these licks at its ultimate pace. Here is the original tempo over which I started wood-shedding.

It took me several hours to get the lick up to tempo. With each new pass, you ratchet the metronome up maybe 3, 4, or 5 clicks until you reach your goal, and the most difficult note sequences require extensive looping in order to achieve smooth, effortless execution.

Here is Jack’s full solo:

As stated above, the band swings like mad throughout this entire performance. Here’s a link, if you want to listen to the whole cut.

Click on “continue reading” below to see a chart of the lick in all 12 keys.

Continue reading “Listen and Learn”Band Bus Banter

On the band bus one day, a buddy criticized me for playing too many descending lines. According to him, “Descending is negative; Ascending lines are much more uplifting.” Oh….really?

Players constantly hear advice like that.

Another commentator assured me, “Your phrase cannot EVER begin on the downbeat; It’s got to be asymmetric.” OK, you win, asymmetric it is, smart guy! The customer’s always right, ay?

One nameless critic insisted, “In order to sound hip, your line has to include several non-harmonic tones.” Still another self-proclaimed “authority” touted the need to stuff many rhythmic devices into your phrase.

Finally, a laconic trombonist named Tex snoring in the back of the bus roused himself from slumber just long enough to drawl lazily,

“How a – bout we try ta swing, Stan?”

So what do you think?

What is it that makes a player sound fresh and innovative?

While listening to the masters and practicing, lines like this one seem to pop out of nowhere. Hit ► below and let me know if it works for you.

Click on “continue reading” below to see a chart in all 12 keys. Or download “New Ears Resolution” to supercharge your ear, so you can play licks like this one in all 12 keys without a chart.

Continue reading “Band Bus Banter”Ben Webster’s “Mellow Tone”

For a chart in all 12 keys, click on “continue reading” below. Or – if you want to learn to play effortlessly without charts, download “New Ears Resolution.”