Guitarist Patrick S. asked for some more examples of “motivic development” (MD). Whether you’re a composer, an improviser, or just looking to enliven your daily practice routine, MD techniques can stimulate your creativity and broaden your musical horizon. Beethoven elevated sonata form to new heights with MD, while Sonny Rollins used MD to revolutionize jazz improv far beyond “a bunch of memorized licks” and “sax players searching for the right note.”

Guitarist Patrick S. asked for some more examples of “motivic development” (MD). Whether you’re a composer, an improviser, or just looking to enliven your daily practice routine, MD techniques can stimulate your creativity and broaden your musical horizon. Beethoven elevated sonata form to new heights with MD, while Sonny Rollins used MD to revolutionize jazz improv far beyond “a bunch of memorized licks” and “sax players searching for the right note.”

Let’s take a look at six ways you can use MD to breathe new life into your music:

- Change the Rhythm

- Alter the “Feel”

- Create Pitch Retrograde

- Offset the Rhythmic Pattern

- Fragment the Phrase

- Sequence the Fragment

If you want to woodshed any of the following examples in all 12 keys, you’ll find complete charts at the end of this post.

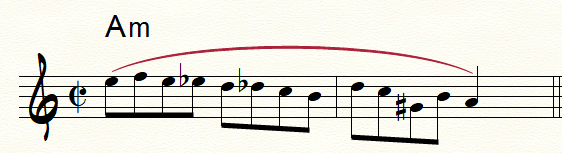

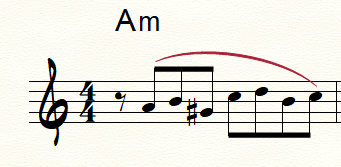

Start with a basic motive. I hit on this one while doodling on the horn. We’ll use it to illustrate MD.

Vary the Feel and Rhythm

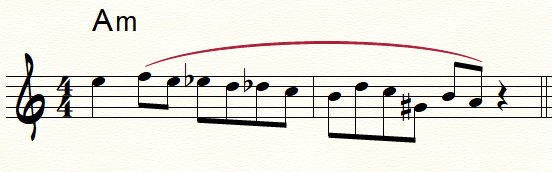

After shedding that lick in all 12 keys, I decided to try it using a swing feel. It quickly became obvious that a bit of rhythmic variation was needed.

Although it’s exactly the same sequence of pitches, adding a swing feel and switching the first eighth note to a quarter note creates a totally different vibe!

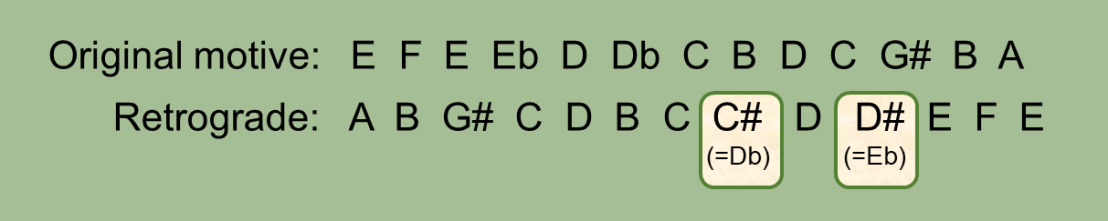

Retrograde

“Retrograde” means playing the notes in reverse order. Here’s a retrograde calculation for this phrase:

The pitches now occur in the opposite order, (although we use the original rhythm). Can you tell this phrase is “cousin” to the original, despite its retrograde sequence of pitches?

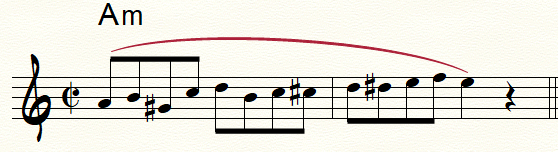

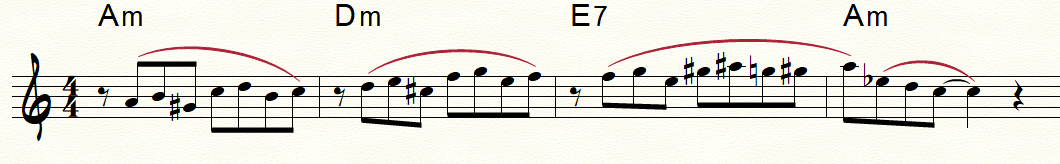

Rhythmic Offset

The retrograde pitch set seemed to lie better in swing time and with a rhythmic offset of ►1/8 note.

Fragmentation

“Fragmentation” involves utilizing just part of the phrase, in this case, only the first seven notes

Sequencing

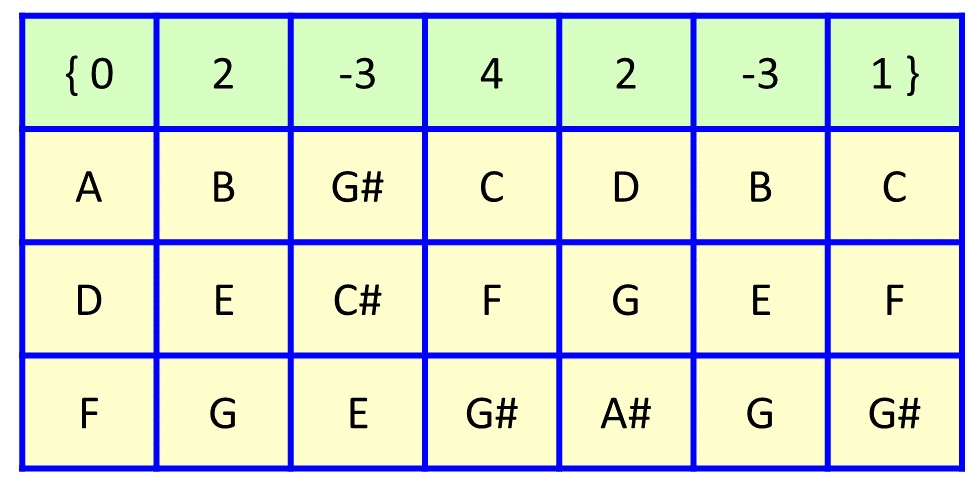

“Sequencing” means repeating a pattern at a different pitch, like “stair-stepping.” The sequenced pattern may include intervals, rhythms, and/or melodic shape. Our fragment has the following melodic shape: It moves up 2 half-steps, then down 3 half-steps, then up 4 half steps, up 2, down 3, and up 1 (shown below in green as

“Sequencing” means repeating a pattern at a different pitch, like “stair-stepping.” The sequenced pattern may include intervals, rhythms, and/or melodic shape. Our fragment has the following melodic shape: It moves up 2 half-steps, then down 3 half-steps, then up 4 half steps, up 2, down 3, and up 1 (shown below in green as

{ 0, 2, -3, 4, 2, -3, 1 }

Using that formula, you come up with the following sequence:

Do you discern the relationship between the initial phrase and this final version?

Would the audience perceive these various iterations as conferring the unity and variety required for a coherent composition or improvisation? Although the relationships may seem subliminal or even obscure, they somehow still contribute unity to a work, when compared with an aimless, stream-of-consciousness ramble.

Please share your ideas in the comments section below.

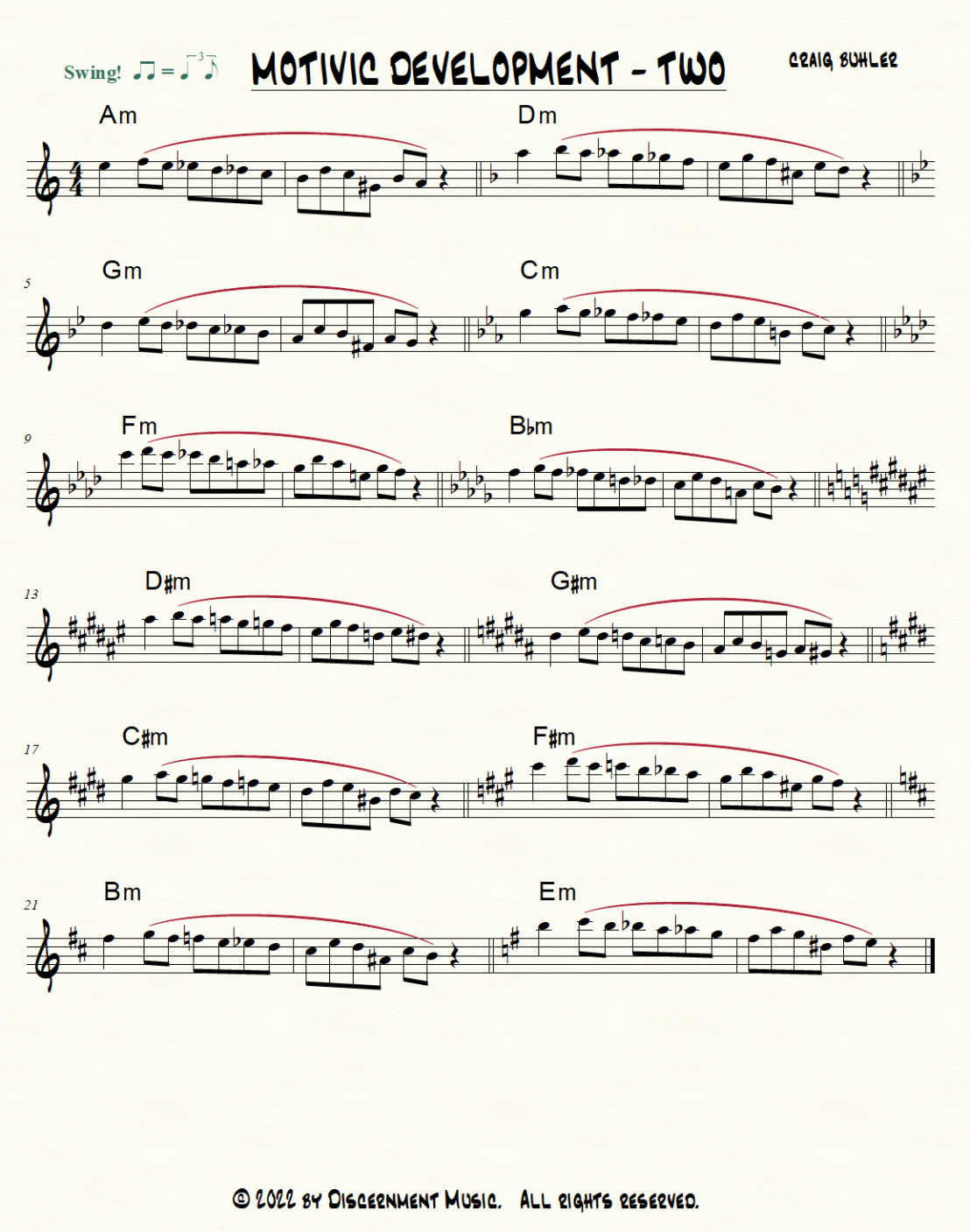

Here are charts to these five exercises in all 12 keys. I played these recordings without charts. You can too, if you work through my revolutionary play-by-ear method called “New Ears Resolution.” Click here for details.

NOTE: B flat instruments begin at bar 1. Concert key instruments begin at bar 5 and cycle back to the top. E flat instruments begin at bar 23 and cycle back to the top.

NOTE: B flat instruments begin at bar 1. Concert key instruments begin at bar 9 and cycle back to the top. E flat instruments begin at bar 45 and cycle back to the top.

I started using this right away in my practice routine. It’s efficient and lets me create new ideas! Thank you Craig.

LikeLike

Glad to hear these are helpful. They sure worked for me.

LikeLike

Very good practice ideas here.

LikeLike