In just 45 minutes, you can revolutionize your understanding of THE HARMONIC LANGUAGE. Learn how chords are created, what notes they contain, how they’re named, and how they’re used to evoke emotion and make music come to life. Quickly gain harmonic mastery and confidence which will set you apart as a composer or improviser.

In just 45 minutes, you can revolutionize your understanding of THE HARMONIC LANGUAGE. Learn how chords are created, what notes they contain, how they’re named, and how they’re used to evoke emotion and make music come to life. Quickly gain harmonic mastery and confidence which will set you apart as a composer or improviser.

Category: Effortless Mastery

Pres says, “Sing me a song!”

Let’s face it, we all want monster chops. There are some great books out there to help develop technique. I work constantly on mastering lix in all 12 keys, but I never play those lix on the gig. That’s not their purpose. The reason for practicing lix is to enhance your facility on the horn and expand your musical vocabulary.

But some of those lix get so obscure, I can’t even tell if I’ve made a mistake in transposing the lick to a new key. That’s when I know the lick is too obscure!

I just got a killer deal on a great classic clarinet mouthpiece. That inspired me to do some long overdue clarinet shedding. I was trying to come up with a lick that felt melodic, one that would swing and sound lyrical, as opposed to clinical.

Let me know what you think of this one.

To see the chart for this lick in all 12 keys, press the “Continue Reading” button.

The Chord Committee

Many, many thanks to everyone who volunteered for The Chord Committee. Numerous excellent solutions have been proposed. In order to avoid discord, I have combined all of your suggestions into one beautiful, majestic chord. In hopes you will find the solution acceptable, the chart and recording are presented here for your approval. (Click on “continue reading” to view the complete chart.)

The Lost Chord

Andy and i were playing this lick the other day.

Andy asked with which chord this lick could be used. I had no answer. Do you?

Got Improv?

You can learn how to improvise like a professional jazz musician! Watch this video to see how you can begin the exciting journey towards becoming a jazz improviser.

Fats Waller & Arpeggios

Mastering arpeggios gives you yet another tool to use (in moderation) in your improv solos.

Mastering arpeggios gives you yet another tool to use (in moderation) in your improv solos.

Have you ever tried playing Fats Waller’s great tune “The Jitterbug Waltz”? Find it on Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s “Bright Moments” album. Mastering arpeggios will make that tune much easier to play.

Here’s a challenging and interesting way to master arpeggios. The idea for this exercise was suggested to me by a warm-up my talented friend Al Thompson often uses.

Click on “continue reading” for a complete chart.

Bonfa, Jobim, and Bossa Nova

Brazilian bossa nova’s introduction to the U.S. thanks to composers Luiz Bonfá (Samba de Orfeu and Manhã de Carnaval), Antônio Carlos Jobim (Desafinado, Girl from Ipanema, Corcovado, etc.), and instrumentalists João Gilberto and Stan Getz literally transformed the jazz landscape overnight.

Brazilian bossa nova’s introduction to the U.S. thanks to composers Luiz Bonfá (Samba de Orfeu and Manhã de Carnaval), Antônio Carlos Jobim (Desafinado, Girl from Ipanema, Corcovado, etc.), and instrumentalists João Gilberto and Stan Getz literally transformed the jazz landscape overnight.

For the past 50 years, casual straight-ahead jazz gigs have invariably featured at least one bossa per set.

Familiarity with the following exercise will greatly enhance your facility with the melodic and harmonic nuances found in these wonderful compositions. Here is the basic lick:

Here is a recording of the lick played in all 12 keys:

Develop your ear to flawlessly play passages such as this one in all 12 keys by downloading and working through “New Ears Resolution.”

TEST YOUR EAR!

You’ll ace this one, if you’ve played through “New Ears Resolution.” If not, it may be tricky.

Below is a recording of the pattern in all 12 keys. Submit a “comment” at the bottom of this post, if you need a chart to play along with the recording.

Note that this phrase traverses the first five chords of the standard “Someday My Prince Will Come,” a long-time staple of Miles Davis’s book. That “harmonic quote” was not intentional. When you start creating patterns in a “stream of consciousness” manner, elements of your repertoire tend to crop up in various guises.

Multi-instrumentalist Kevin McCartney recently taught me about the ebb and flow of tension and release created by Cuban clave patterns. In this exercise, the many accidentals create a bit of harmonic tension, which is then released through resolution to adjacent diatonic notes. Note in particular the tension created by Si, Di, and Le.

Upon further reflection today (during surgical anesthesia!), it occurred to me that this phrase uses all 17 notes in the scale: the 7 diatonic pitches, the 5 sharps, and the 5 flats. For a horn player, G# and Ab are identical. However, a symphonic violinist thinks of them quite differently.

What you hear in this recording is actually 5 clarinets. Took me about 20 takes to get 5 usable ones.

Dig Jimmy Heath!

Jimmy Heath is another master with whom I hope to become more familiar.

Jimmy Heath is another master with whom I hope to become more familiar.

Driving into a glorious autumn dawn on the way to church Sunday, I was listening to “Picture of Heath” and was particularly struck by the third chorus of Jimmy’s soprano solo on “All Members.”

I don’t usually go to the trouble of formally transcribing solos, since there are so many fine transcriptions available on-line. But Jimmy’s third chorus really knocked me out, and i felt compelled to examine the strategy, structure, and logic of this amazing 12-bar chorus. Continue reading “Dig Jimmy Heath!”

Mastering Modulation

Have you ever ridden on a roller coaster blindfolded? That’s how it feels to improvise without understanding internal modulation. It’s like driving through a thick London fog. Progress is halting, movements are uncertain and tense.

By contrast, the player who understands how to navigate key changes improvises smoothly and confidently.

This month, we learn to recognize an internal modulation and craft an effective response. Continue reading “Mastering Modulation”

Developing Hand – Ear Coordination

Do you want your improvised solos to soar and delight your audiences? The first and most important step to achieve this is to develop the link between your ears and your fingers. In fact, ultimately we need to be able to transfer any musical idea we imagine to our fingers. I call this “Hand-ear coordination”.

What is “Ear Training”?

It is a thrilling moment when a musician first experiences the freedom of playing without reliance on the printed score. To be able to play a melody by ear or to spontaneously create an improvised solo never before heard provides joy not to be missed by the player committed to musical excellence.

Transposing Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” Using New Ears

A question just came in from a user of New Ears Resolution as to how he could use movable DO to transpose Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation.” (His letter is posted below.)

Continue reading “Transposing Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” Using New Ears”

RIPPING RIFFS OR MEMORABLE MELODIES?

Craig wrote this article for the February, 2016 issue of Saxophone Life Magazine. It appears here courtesy of SLM.

Craig wrote this article for the February, 2016 issue of Saxophone Life Magazine. It appears here courtesy of SLM.

It’s definitely impressive to hear jazz musicians improvise at incredibly fast tempos. What is, however, far more inspiring is hearing how the great masters are able to create beautifully crafted, swinging melodic lines, regardless of tempo. Continue reading “RIPPING RIFFS OR MEMORABLE MELODIES?”

Learning to Play by Ear: A 1958 Perspective

How does a musician learn to perform thousands of songs in any key without looking at music sheets? How can you improvise over a set of “changes” you’ve never heard or seen before in a live performance? “New Ears Resolution” has made this a daily reality for me during a 40-year career of recording dates and live performances. But I cannot claim to have created this revolutionary approach to ear training. I learned it during high school while studying with Alvin L. “Al” Learned, founder and president of Hollywood’s legendary Westlake College of Music “one of the most important educational institutions for the study of jazz in the post-World War II era.” Continue reading “Learning to Play by Ear: A 1958 Perspective”

How does a musician learn to perform thousands of songs in any key without looking at music sheets? How can you improvise over a set of “changes” you’ve never heard or seen before in a live performance? “New Ears Resolution” has made this a daily reality for me during a 40-year career of recording dates and live performances. But I cannot claim to have created this revolutionary approach to ear training. I learned it during high school while studying with Alvin L. “Al” Learned, founder and president of Hollywood’s legendary Westlake College of Music “one of the most important educational institutions for the study of jazz in the post-World War II era.” Continue reading “Learning to Play by Ear: A 1958 Perspective”

Darn That Dexter!

Dexter Gordon is universally revered by saxophonists for his muscular sound. He is equally effective on ballads, blues, and fast tempos.

Dexter Gordon is universally revered by saxophonists for his muscular sound. He is equally effective on ballads, blues, and fast tempos.

His Blue Note LP One Flight Up includes a fine reading of the Jimmy Van Heusen ballad “Darn That Dream” on which he dexterously employs a device favored by Charlie Parker. This maneuver involves momentarily raising the key a half-step and inferring a ii-V progression in that key.

Here are two instances in which Dexter deftly employs that ploy. As anyone who has ever tried to transcribe his solos knows, one of the hallmarks of Dexter’s style is his unique approach to rhythm. While his languid phrasing is pure joy to hear, it’s a nightmare to transcribe. I have greatly simplified the rhythm in these two examples, focusing instead on the pitches Dexter chose for the brief modulation. Continue reading “Darn That Dexter!”

“Remember” Hank Mobley’s “Soul Station”?

The road to dynamic, expressive improvisation is paved with practice and listening. Hank Mobley’s near perfect solo on Irving Berlin’s “Remember” from his classic LP “Soul Station” is filled with profound lessons on phrasing, rhythm, tone, melody, pacing, and development. Here is just one of the great ideas you will encounter when studying this wonderful recording.

The road to dynamic, expressive improvisation is paved with practice and listening. Hank Mobley’s near perfect solo on Irving Berlin’s “Remember” from his classic LP “Soul Station” is filled with profound lessons on phrasing, rhythm, tone, melody, pacing, and development. Here is just one of the great ideas you will encounter when studying this wonderful recording.

As always, we recommend learning the phrase in all 12 keys. Practice with the audio file found below. Continue reading ““Remember” Hank Mobley’s “Soul Station”?”

As always, we recommend learning the phrase in all 12 keys. Practice with the audio file found below. Continue reading ““Remember” Hank Mobley’s “Soul Station”?”

Why Is This Tune So Hard To Memorize?

Have you ever had difficulty playing a tune, even though it presented no obvious technical hurdles? Perhaps the problem lies in a hidden harmonic riddle, which, when solved, will unlock your understanding of the song and make it easier to play and to remember.

At a recent gig, pianist Mark Schecter called off Dizzy Gillespie’s “Groovin’ High.” Although Storyville used to play the song, it still made me stumble. However, after deciphering its harmonic implications, playing it became simple.

Here’s how to solve a riddle like that.

How to Learn Songs

Is there a more effective, efficient method for learning and retaining a large repertoire of jazz standards? Continue reading “How to Learn Songs”

Dominant Seven Flat 9 Chords V7(b9)

One of the features that makes a minor key sound so rich is its V7(b9) chord illustrated below as a V-I in the key of A minor. ![]()

The exercise shown below will greatly increase your familiarity and confidence in improvising over this lovely chord. Continue reading “Dominant Seven Flat 9 Chords V7(b9)”

HOW I LEARNED TO PLAY BY EAR

Even many accomplished musicians never learn the fine art of playing by ear. A strong ear is a “must” for those of us musicians with visual disabilities. I owe my ear to a uniquely inspired teacher. The story begins in 1963. Continue reading “HOW I LEARNED TO PLAY BY EAR”

Thematic Development Galvanizes Your Solos

Do your solos brim with vitality, gliding across a colorful landscape, as you explore ever deeper into the ocean of sound? Or do you flounder among waves of notes, swimming through a maze of chord changes?

Do your solos brim with vitality, gliding across a colorful landscape, as you explore ever deeper into the ocean of sound? Or do you flounder among waves of notes, swimming through a maze of chord changes?

Thematic development will transform your playing, as you weave your exciting, personal story.

Thematic development will transform your playing, as you weave your exciting, personal story.

The following clips illustrate three powerful tools to stimulate your creative potential and enthuse your audience.

1. RHYTHMIC SHIFT – Example 1 presents a 7-beat phrase that starts on the “and” of beat 3. The phrase is then repeated, but this time, it begins on the “and” of beat 2. Repeating the phrase gives your thought unity, while the rhythmic offset offers variety and surprise. Try playing along with this recording in all 12 keys.

2. DIMINUTION – In example 2, the 7-beat phrase is the same, but a triplet compresses the second statement of the theme. Your motif is still easily recognized, but you have added variety.

3. TONAL SHIFT – In Example 3, the second statement of the theme modulates up a minor third. Tonal shift was a favorite device of John Coltrane. The listener still recognizes your theme, but her ear delights in this fresh new element you have added to the mix.

As you become more comfortable with creating and developing thematic material, your unique personality defines your individual style. You improvise dynamically and coherently.

To master these 3 techniques, play along with the 3 audio files offered here. Contact me, if you need a chart. Or, if you want to learn to play by ear in all 12 keys (as I did while recording these clips), download “New Ears Resolution” and liberate your musical imagination!

Do You Enjoy Practicing Scales?

How often do we teachers hear students complain about having to practice long tones and scales? Every teacher knows that long tones greatly enhance tonal quality and intonation and that scales are the raw material from which improvised solos are crafted. The problem is that any musician who practices being bored will bore the audience. What you practice is what you perform. Practice joy, imagination, and freshness, and your show will be fresh. Practice dry technique, and your gig will be a desert.

Below is a 4-bar phrase containing a descending major scale (Ionian mode) and an ascending Mixolydian mode. I worked on this exercise until the rhythm and note sequence started to feel interesting to me.

Try playing along with the background track provided below and see if this approach adds a bit of zest to your practice time. Develop your own variations on this idea. Email me for a FREE copy of this exercise in all 12 keys, if you have trouble figuring it out. Better yet, download “New Ears Resolution” and learn how to play any melody in any key by ear.

Happy New Year, Sonny Rollins!

What a great way to ring in 2015! We watched “Labor Day” on Netflix, and then I revisited Sonny Rollins’ 1998 CD “Global Warming.” Sonny has a wonderful ability to compose simple melodies that swing. And, of course, the unique way he develops motivic material during his solos is legendary. Solos brimming over with life and joy. I just had to pick up my horn and play along. Here is the lick that emerged, Adolph Sax’s new year’s gift.

Try playing along with this melodic minor phrase in all 12 keys using this background track. If you have trouble transposing it, email me for a free chart. Or download “New Ears Resolution” and learn how to play any melody in any key by ear.

Try playing along with this melodic minor phrase in all 12 keys using this background track. If you have trouble transposing it, email me for a free chart. Or download “New Ears Resolution” and learn how to play any melody in any key by ear.

Improvising Using Skips

Are your improvisations based more on the chord changes (Coleman Hawkins approach) or on the melody (Lester Young approach)? Many players look at the chord progressions and derive either arpeggios or scale patterns based on the indicated changes. Here is an exercise that will develop your ability to integrate larger leaps into your melodic flow.

To derive the maximum benefit, practice this pattern in all 12 keys around the circle of fifths using the background track provided below. If you have difficulty figuring out the pattern in the other keys, contact me for a FREE chart (no cost or obligation). Better yet, download “New Ears Resolution” to learn how to play any melody in any key BY EAR!

Check Out This Great Saxophone Web Site

Jeff Rzepiela is a talented reed player and arranger. His web site contains many transcriptions of solos by the masters of jazz. Check out his latest newsletter Scooby-sax_Newsletter_Oct_2014(1) which features an insightful analysis of an improvised solo by Arnie Krakowsky over the tune “I’ve Never Been in Love Before.” Jeff skillfully singles out several key phrases in the solo, shows how they relate to each other, and makes them available for those of us who benefit from “wood-shedding” over great “licks.”

Be Part of a Jazz Big Band!

Are you or your students or friends interested in big band music? Please help me spread the word about a unique opportunity to join with like-minded musicians in making some swinging music and having a good time to boot. They say the setting is beautiful and the food is great! Many of the players return year after year.

A Jazz Lick From Bach? Yes Indeed!

A recent biography of jazz tenor sax giant John Coltrane verified that he had indeed studied the wonderful Bach Cello Suites. The suites, though quite challenging, are a joy to play, and they provide numerous opportunities to build your tone, technique, and conception. As it turns out, they also contain some amazing phrases which can be adapted as jazz improv “licks.” What do you think of this one? It’s from Bach Cello Suite Number 2, “Allemande,” bar 21. Play it through in all 12 keys (see chart below) and let us know whether Bach gives you ideas for your jazz improvisation.

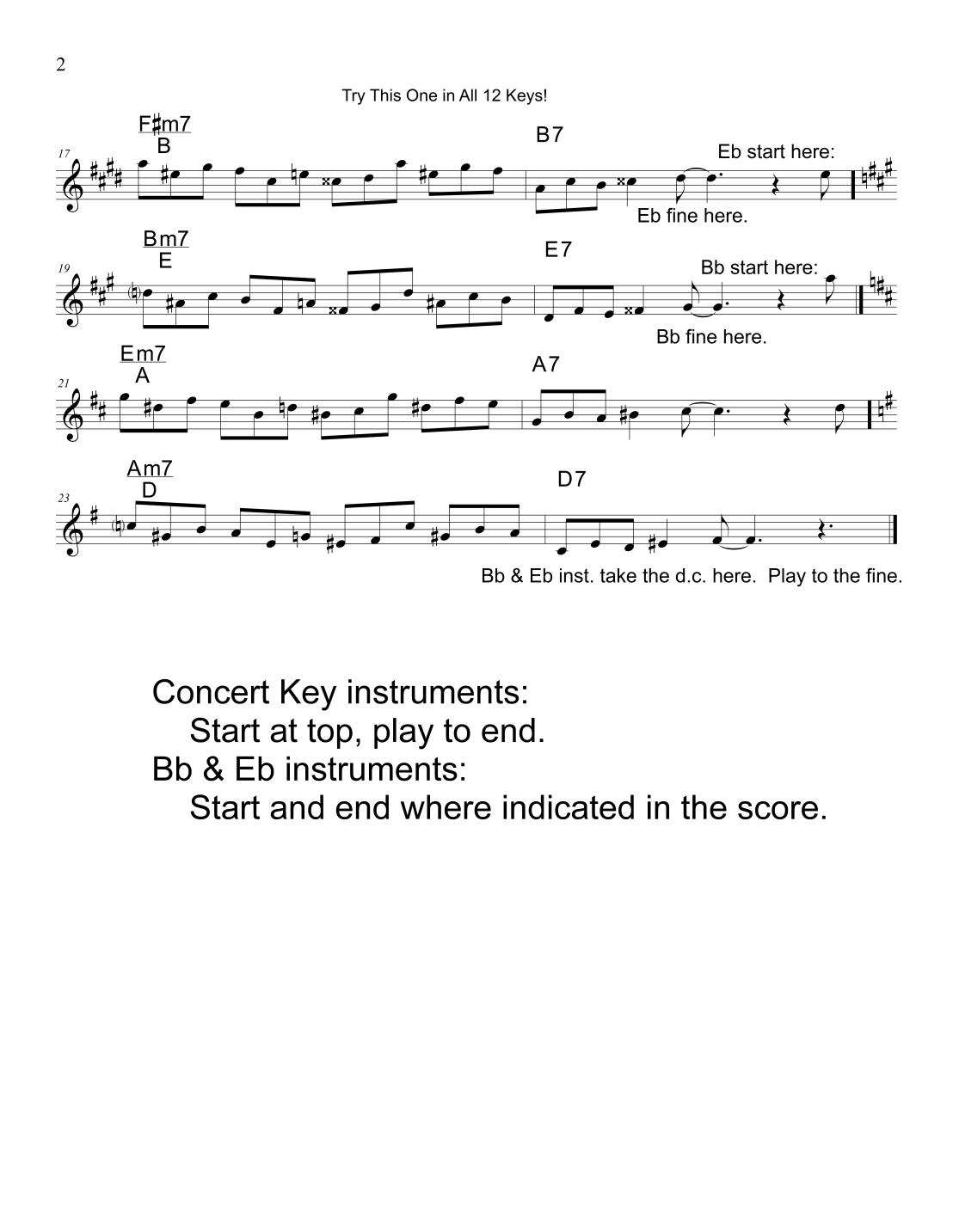

Try This One in All 12 Keys!

Here is an interesting phrase I’ve been practicing in all 12 keys. As always, follow Kenny Werner’s cue to “play effortlessly” in order to get a relaxed, flowing, swinging feel. Try playing along with the background track provided below. If you need a chart, it is also provided below. Better yet, download “New Ears Resolution” and learn how to play in all 12 keys by ear with ease.

Noted Guitarist Praises “New Ears Resolution”

This review of the Second Edition of “New Ears Resolution” was posted by the wonderful guitarist, singer, and educator Trevor Hanson http://trevorhanson.com/trevor/ . Trevor is highly respected for his work in both the jazz and classical fields and has a large following in Western Washington State.

- Basic concept: great. The basic concepts and the way you have organized their presentation are very useful. You have many good insights and analogies to help get students on board, even if they have had little formal training. There’s no question that moveable-do solfege is a tremendous learning aid, and you’ve done a good job at making it accessible and understandable. The early parts of your presentation assume that the reader has little or no background in music theory.

- Combining essential skills in small lessons. By combining ear training, scale/harmony theory, and repetition and presenting the material in small, easily manageable chunks, you’ve provided an excellent framework for learning that doesn’t overwhelm the student. Many theory books cover this material in just a few pages – making it difficult for students to achieve a working knowledge of (and quick memory for) these essential elements.

- Familiar tunes as examples. Linking little phrases to familiar tunes is very helpful. This is how most of us recognize intervals, patterns, and progressions. By providing examples, you save students time, since recognizing a short quote is often difficult.

- Audio files. Listening to and playing along with the audio files is a huge advantage.

- Scale/chord material. Your presentation of the scale modes is very good. I really like the clear examples showing how each mode can be derived from the Ionian, the examples showing how each modal color can be used, and the charts/audio exercises that contrast these elements. I found your discussion of Locrian m7(b5) and Phrigian sus(b9) even more useful. I ran out of time before getting a chance to look at Bill Green’s approach to the blues scale and V7#9#5 chord, and am looking forward to examining this section. These are all really important topics that most musicians just have to figure out by experimentation. You have provided a logical starting point for studying these elements.

Sincerely,

Trevor Hanson

www.TrevorHanson.com