Last month, we looked at the major scale, which has been foundational to Western music for 400 years. Each of the 7 notes in that major scale can function as the root of a diatonic chord. A basic understanding of those 7 chords will greatly improve your ear and your improvisatory skill, so let’s focus on them this month.

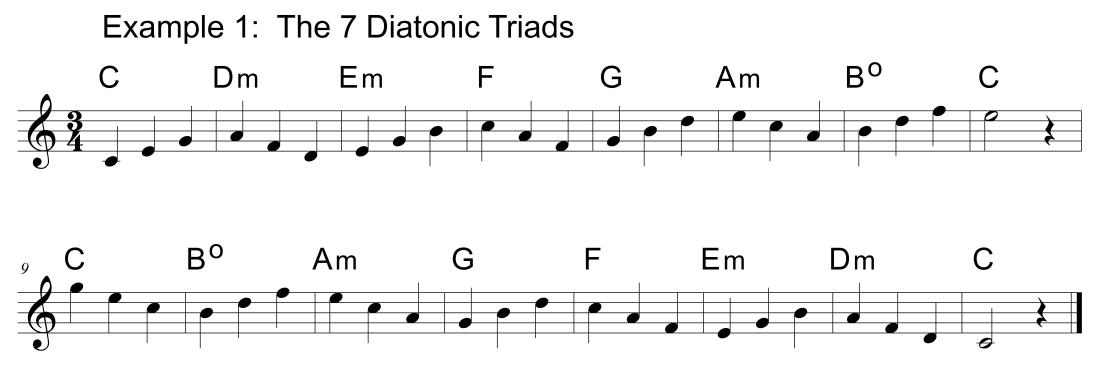

A “triad” is a chord containing three notes. Try playing the 7 diatonic triads shown in figure 1. Can you play them in other keys as well?

The 7 chords shown here are all in “root position,” meaning the root is the lowest note. The beginning of “The Star Spangled Banner” features a root-position triad (see figure 2). By contrast, “In The Mood” uses a first inversion triad, with its root on top. The bugle call “First Call” begins with a second inversion triad. Its root is the middle note.

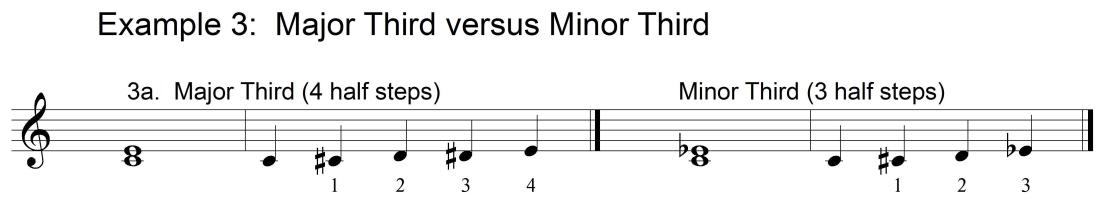

In order to distinguish major chords from minor, you need to discern between major and minor third intervals (see figure 3). Notice that in a major third interval, the notes are 4 half-steps apart, while in a minor third interval, the notes are only 3 half-steps apart.

Figure 4 shows the 7 diatonic triads. The gray boxes show you how many half-steps separate the notes. For example, between DO and MI, there are 4 half-steps, a major third interval. Between MI and SO, there are 3, a minor third interval. A triad with a major third below and a minor third above is a major triad. Figure 4 has three major triads. They are built on the roots DO, FA, and SO. Can you play the DO, FA, and SO major triads in several keys?

Look at the triad built on RE. There are 3 half-steps between RE and FA (a minor third interval) and 4 half-steps between FA and LA (a major third interval). A triad with a minor third below and a major third above is a minor triad. Three minor triads are shown in figure 4, those built on RE, MI, and LA.

As you play these major and minor triads, try to hear the difference. To folks raised on Western music, major triads generally sound “happy,” while minor triads tend to sound “sad.”

Now look at the triad built on TI. Between TI and RE, there are 3 half-steps (a minor third interval). Between RE and FA, there are also 3 half-steps (another minor third interval). A triad built from 2 minor third intervals is called a “diminished triad” (because the intervals have been “diminished” – (made smaller).

Figure 5 shows the triad built on FA. Additional pitches have been stacked on top of the triad. These notes are referred to as “extensions.”

The extensions are numbered as if they were degrees of a scale starting from the root. We’ll discuss many of the extensions in a later issue.

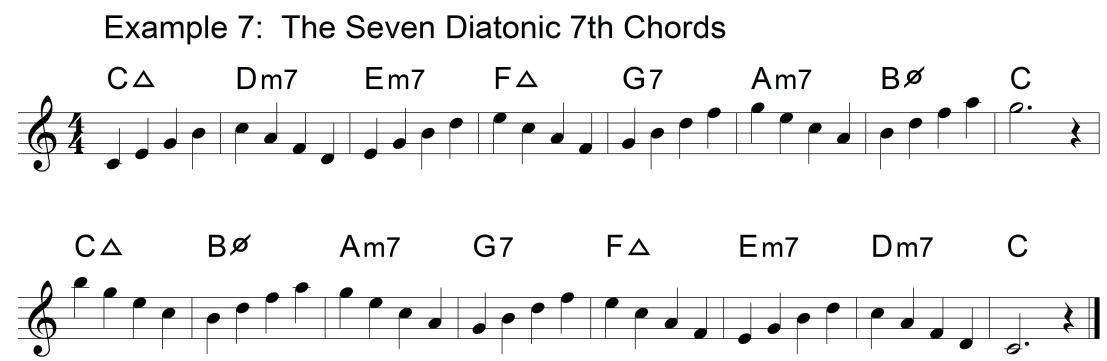

For now, let’s focus on the 4-note chords known as “7th chords.” There are three types of diatonic 7th chords contained in the major scale, as shown in figure 6.

The root of each chord is shown in yellow, the third in purple, the fifth in green, and the seventh in blue. Notice that between these chord tones are either 3 or 4 half-steps. Once again, the smaller interval is referred to as a “minor third,” the larger is a “major third.” Below each chord, its type is shown in dark blue. Major 7th chords are built on DO and FA, minor 7th chords on RE, MI, and LA. The dominant chord, built on SO, is very special, as it determines what key you are in. (More on that in a moment.) The chord built on TI is referred to either as “minor 7, flat 5,” notated as m7(b5), or “half diminished,” notated as Ø .

Play through these chords as shown in figure 7. After playing them several times, you will begin to hear the different sound of each type.

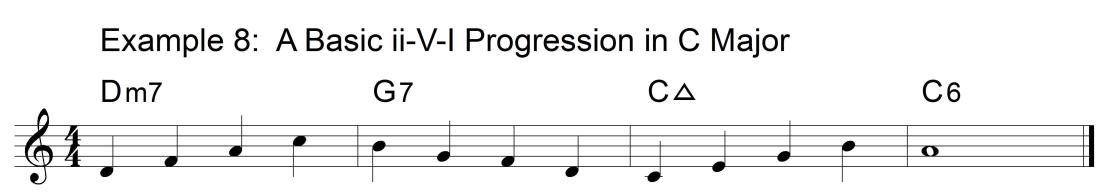

The most important chord progression in “The Great American Songbook” is the ii-V-I progression (pronounced “2, 5, 1”). Figure 8 shows a basic ii-V-I progression in the key of C major.

Notice that the G7 chord contains both B natural and F natural. In reviewing the Circle of Fifths, it becomes clear that only C major contains both of these notes. This “tritone,” as it is known, defines the key of C major. Every ii-V-I progression has a similar tritone which defines its major key.

As you look through The Real Book, make it a habit to search for these ii-V-I progressions and to note the major keys they suggest. This will guide you in selecting the major scale to use for that portion of your improv. Several examples are illustrated in figure 9.

Now for this month’s “puzzler.” How many of the following melodies can you identify? The answers will appear in next month’s edition of Saxophone Life.

- MI RE DO, MI RE DO, SO FA FA MI, SO FA FA MI, SO DO DO TI LA TI DO SO SO, etc.

- SO LA SO FA MI FA SO, RE MI FA, MI FA SO, SO LA SO FA MI FA SO, RE SO MI DO.

- DO SO DO SO DO RE MI DO. FA FA DO RE MI, etc.

- SO SO FA MI MI RE DO DO TI LA SO, etc.

- DO RE MI LA LA, SO FA MI DO DO, DO RE MI TI TI TI TI DO TI DO LA SO SO, etc.

- DO RE MI SO SO SO SO RE, DO RE MI SO SO SO SO FA, etc.

- DO RE MI SO, MI MI RE DO MI, DO RE MI LA, SO SO FA MI FA RE, etc.

- RE MI RE MI RE LA LA, SO LA SO LA SO RE DO TI LA, etc.

[1] For the sake of brevity, this discussion is necessarily oversimplified and restricted to jazz practice. For more detail, consult https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consonance_and_dissonance , in particular, the paragraph mentioning George Russell https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consonance_and_dissonance#Neo-classic_harmonic_consonance_theory